IDOC Type:

In Folders:

Adham Hafez could not make it to the Symposium. However he was able to present his work via Skype encouter. As a gesture of generosity towards idocde and idocde guests, he sent the full text so that we could later dig into the context notes in the text, in case we have questions that we could not ask in his lack of physical presence! We thank Adham and all the Symposium guests who attended this impressive online presentation!

Tahrir Square- January 2011

"I have to be a fallen woman who’s really successful"

Amie Sultan

1. Olim Lacus Colueram

“Olim Lacus Colueram. Olim Pulcher Extiteram. Dum Cygnus Ego Fueram.[1]”

These are the opening lines to the aria of the swan from Carmina Burana by Carl Orff, to which a male chorus with a deep voice replies: Miser, modo niger, et ustus fortiter. Miserable, and your fate is black, and you shall be roasted fiercely, would be the closest English translation.

This would be the last song and the last time I sang for the Cairo Opera house as their countertenor, who was often scolded for how morality and society will be traumatized by my voice; a voice that troubles seated notions on gender and public decency in Egypt now, where I eventually stopped singing. I was educated at the Cairo Opera House, studying contemporary dance and western classical Opera. After this event, I moved to work within cabarets and nightclubs where it was possible for me then to perform without having to immediately deal with public morality or with the nature of what it is to be an ideal Egyptian. Since then, no other countertenor was hired, and given that I was the only Egyptian countertenor to have graduated from an Egyptian music institution, no other men have performed –or possibly will perform in any near future- the full repertoire of countertenors and castrati there. It is more decent that way, according to the Opera House, and less disturbing to public morality perhaps. And, while Cabarets in Egypt have historically played a crucial role both in producing dance and music that challenged the social and musical normative expectations, as well as produce sites for alternative forms of anti-colonialist resistance, they always remained sites outside of recorded art history. Those havens, those schools, those cracks in the walls of tyranny, those cabarets…! This does not mean that they ever were seen apolitically. On the contrary, from the days of Kuchuk Hanem, going through Shafiqa Al-Qebteyya, and arriving to Tahia Carioca, Samia Gamal, and up until a dancer called Amie Sultan. And since Cairo is Cairo, both magnificent and absent from what is described as ‘art history’ internationally, one must resort to socio-political history to look at artistic practices, not merely to situate them contextually, but to retrieve incidents and look at art-history trajectories.

A Tale of Two Cities

While English novelist Charles Dickens looks through his work "A Tale of Two Cities" on Paris and London at the time of the French revolution, retracing ideological changes and societal upheaval, one could think of the history of Cairo through this metaphor of two cities but condensed in one. A Tale of two Cities within one City. A Tale of two Cairos.

To be able to grasp the multiples that Cairo city is, and to continue on the thread of revolutionary and urban change Dickens' title suggests, I propose another tale to be written: "A Tale of Two Opera Houses". Cairo Opera House of the 19th Century, and Cairo Opera House of the 20th Century. Both Opera Houses were erected to monumentalize ideals of what Egypt stood for culturally, and to mark imperialist international relationships, giving architecture to grand narratives.

Royal Egyptian Opera House- Erected 1869, Burnt 1971

Both two Operas stand -in memory and on the ground- to narrate tales of two Cairos, with multiple epistemological ruptures generated through violent regime shifts. The first Opera House is the Khedivial Cairo Opera House, established 1st November 1869. Marking the opening of the Suez Canal, the Khedive of Egypt ordered the building of the Cairo Opera House in 1869. Designed by Italians Pietro Avoscani and Mario Rossi, the Opera House commissioned world-renowned composers, most of famous of this list is Giuseppe Verdi, who opened the House with Rigoletto, until the completionof the commissioned work Aida that was later performed in 1871. Exactly one hundred years later, this Opera House was set on fire on its four corners, burning it down to ashes, while it burnt on the same square that has the central firefighters headquarter. A new Cairo was to be established, but neither did Khedive Ismail Pasha -the ruler of Egypt at the time- nor Verdi could have imagined what future was to later come.

At the time of the Khedive Ismail, a new Cairo was being constructed also, that was given two names; Paris-sur-Nil, and Ismaileya. One name denotes a city that is to emerge into a 'modernity' that was started by Ismail Pasha's family founder; Mohammed Ali Pasha, and is to surpass the symbolic capital of European beauty; Paris. The city of light was to be replaced by the city of the Nile. Khedive Ismail's investments in securing Egypt's supreme position in the East/ West relations clearly necessitated the anchoring of it not only in architectural edifices (very few of which were national monuments), but rather in the domination of being able to produce, commission, own and disseminate European culture. This should stand as a reminder of a similar monarchic strategy taking place in our world now, with the purchasing and erecting of a Louvre in Abu Dhabi. Arab monarchs performing the same strategy of -literally- buying European art, and paying the highest price to physically house the canon, or at least large parts of it as is the collection of Louvre. For the performance to be complete, and to grab the west from both ‘horns’, the purchasing and erecting of ‘a’ Guggenheim is necessary: For the canon is in Europe and is in the US, and hence the performance of ownership must include both territories. Colonialism is as complex as such multitudes of performances and of ownerships, of reenacted roles, and vested role-play. Like Walter Benjamin reminds us: “Only a thoughtless observer can deny that correspondences come into play between the world of modern technology and the archaic symbol-world of mythology.[2]” Is it at all a coincidence that the Louvre’s name itself refers ‘a place where wolves were hunted’[3]?

Travelling back and forth through time stretched on Egyptian sands and lands, "La description de l'Egypte", the great literary and scientific project of the Napoleon invasion of Egypt, and the formation of the “Institut D'Egypte”, where crucial factors to the eventual establishment (or repurposing) of the Louvre as a museum. It is almost frighteningly prophetic that for the Louvre to be erected, Napoleon had to return to the 'mother of all civilizations', and to describe it, notate it and draw it. Egypt had to be represented and framed, to create a historical genealogy. The museum opened on 10 August 1793, the first anniversary of the monarchy's demise. A place were wolves are hunted, is opened on the anniversary of the fall of a monarchy. Such a contested house of wolves must be hence re-owned by Arab monarchs. Are they announcing the demise of a current monarchy, that not only is invaded by its own making of radical Jihadism, but is also ready to monatize an emblematic icon of its cultural capital and franchise it? Is the purchase of the house of wolves by Arab monarchs, a return to the primary deserts that gave birth to the Louvre in its first place? Is this return to the primary site of frame production, or a fall into neoliberalism? Is this the end of a long colonialist expedition, or is this just the age of monatizing everything including 'cultural heritage'? Has this cultural heritage been built on anything other than colonialism, violence, and the othering of nations on the sunnier side of the European empire?

Worth mentioning as well is that the Louvre's first director is Vivant Denon; the founder of Egyptology, and the man that sat on the arts and literature board of the infamous "Institut D'Egypte". To erect the house of the wolves, one must appoint an expert on the wilderness that is Egypt, in order to capture the wolves. That is the ‘neither the orient nor the occident’, an ontological wilderness confusingly physical situated as a geopolitical portal to the constructs deemed East and West.

Louvre Abu Dhabi- Construction in Progress

In 1970: Sadat took over the presidency in Egypt.

In 1971: the Royal Opera House, which is the Khedivial Opera House, which is Africa's first Opera House, which is the Middle East's Opera House, which is the first Arab Opera House, which is the Cairo Opera House, simply was set on fire at its four corners. It burnt down to ashes, causes of fire unknown, while it rested on the same square across from the central unit of firefighters. Not a hose was lifted to extinguish the fire, and the few late hoses that did show up, where punctured by holes -mysteriously- making it impossible to stay erect and gush enough water to save the burning building. Within one day, one Cairo Opera House was turned to ashes, eradicating the possible history of what had been, to make the future -that has been tilting since Nasser's 1952 military Coup- to fully collide with space and bring about a new regime. This time, bringing about a new aesthetic regime.

On the site where the Opera House stood, a public garage was built by the regime in power.

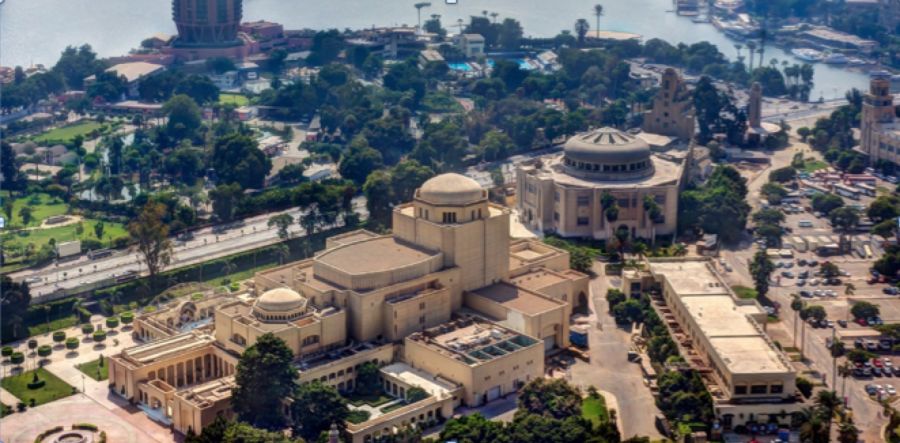

Cairo Opera House came back to life in 1989. Financially bestowed on Egypt as a gift from the Japanese Emperor, the new Opera House was to be established by the Nile. On the Island of Zamalek, that was the botanical garden of the empire, the new house was to built as a complex of theatres, that –again- were to sustain the State in existing through performance. Not only by centralizing –again- the performance of politics, but also the power to perform, in the post-ideological Egypt of the Mubarak regime.

Cairo Opera House- Zamalek, Cairo

2. Olim Pulcher Extiteram

“Olim Pulcher Extiteram”; once upon a time I was beautiful.

Exhausted by violence, forced performances of idealism for the sake of regional economic-political interests, and living in a reality that undermines life, millions of Egyptians have marched against their misrepresentation, against nostalgic narratives, and against beautiful lies. In 2011 a massive protest escalated into a political movement with a revolutionary force that toppled the regime of the Mubark family that has been ruling Egypt from 1981-2011, through a regime of documented systematic violence from the state against any civic opposition. The acts of violence include disappearances of activists, rape of protesters (male and female), exile, travel bans, censorship on the arts, and other. Such –inherited- violent practices are the product of the fall of the Nasserist project, and Sadat’s police state as response to the ideological vacuum that Nasser’s death left. In 2011, during the uprising that later came to be described as the Arab Spring, an orientalist title that included within which the budding Syrian Revolution that had turned into an ongoing war and global human crisis, the fall of Yemen to civil unrest, and the collapse of the Libyan State. There was no spring in the uprisings in Cairo, Tunis, Damascus, Tripoli or Aden. The movement(s) of necessary political change came about because of driving demographic factors in the Arabic speaking region. In Egypt, as it is the focus of this text, one sees this clearly. Such demographic factors include the fact that 75% of the population of the megalopolis of Cairo is under the age of 30, with no work prospects living under a crumbling state. In the absolute lack of state structures that would support youthful movements to flourish and re-inscribe the land known as Egypt, and yet in the overwhelming presence of over 40,000 non-governmental organizations that since the rise of Sadat's market driven regime, also could be described as neoliberal military capitalism; the 40,000 NGOs that were born are necessary structures that have replaced the state in many of the basic services needed by the citizens; education, health, social work, and arts.

One could trace the failure of the Mubarak regime in its failure to mend the wounds of the country’s infrastructure. Argued to be traced to the 1968 war failure, the Naksa[4]; the infrastructure suffered greatly through multiple attacks on Egyptian lands by occupying forces. This gradual decay of the State is traced within several urban studies theories to be the moment where the ‘informal settlements’ began in Egypt. A population fleeing war in many towns in its own homeland, living within a war-torn region, is forced to relocate within the very same country, creating massive waves of internal displacement, within a crashing economy investing only in war. Fleeing the war, such populations may have grown disenchanted with a glorious para-colonial past, and propagandist regime. Citizens at such times learn to reconstruct life on new terrains and with tools that are foreign to the sites of their immigration and exclusion, perhaps could be unfolded through Anurima Banerji’s work on the notion of the ‘paratopia’. They no longer live by a beautiful lake, and they are trying to survive. In their acts of survival, tools from the capital are re-purposed and misused, producing realities that the capital cannot fathom.

Ashwa’yaat (informal settlements) generally described as informal urbanization and expansion beyond the regulations and the scope of the State. According to Marion Sejourne’, such settlements as of 2006 house more than 65% of the population of Cairo[5]. And, while official narratives and counts on minorities and displaced peoples in Egypt take into account as precisely as how many British citizens live in relation to how many Nubians do in the South of Egypt, such accounts constantly resist producing exact counting of the ‘informal settlers’. Is it because the State would rupture its performances of ideal Statehood if it did? Or is it perhaps that the State itself cannot produce such counts without having to enter the ‘paratopia’ that it often denied its existence?

With over 1200 settlements in Egypt, with collapsing units and a density beyond that of Cairo, one wonders how the State continues to operate within this; A Tale of Two Cities. A Tale of Two Cairos, this time seen outside of the history of Egyptian Opera, and rather the history of Egypt torn between its citizens’ performance of their selves, and the pre-assigned and pre-choreographed performances of self laden on the bodies of the citizen by the State’s propagandist apparatuses, from Operas, to linguistic institutes that continue to ignore Egyptian as a spoken lived language.[6]

With the end of the Nasserist regime in Egypt, and the rise of Sadat into power timed to the surge of the petrodollar and the nascent gulf states, Egypt witnessed its first mass immigration in modern times. Millions of Egyptians relocated within gulf states seeking better economic realities, in order to support their households in Cairo. Engulfed in the Wahabist middle class ethics and body politics that the gulf continues to perform, the ‘economic immigrants’ upon their relocation in Egypt would be yet another opposing force that highlights the necessity to perform certain ideals to please State structures. Such performances by the State and by the returnees would eventually diminish in number in relation to the encroachment of the ‘Ashwa’yyat’ on the official capital. Diane Singerman explores in her book “the Siege of Imbaba”, how public discourse coupled with the performance of social propriety continued to generate an Egyptian ‘other’ within the very fabric of the nation. In this demonization and othering of the majority of citizens in order for an official narrative to survive and for reality to remain undocumented, we produce simulacra of existence, and we produce a continuum of lies that beget violence. Michel Foucault points –more than once- at how stigmatization tends to be used as a political utility, which resonates with the reality lived by Egyptians from the ‘fall of the State’ and up until today. The millions that marched against Mubarak, marched against simulacra of existence, and the continuum of lies, and the latent violence.

3. Dum Cygnus Ego Fueram

“Dum Cygnus Ego Fueram”; When I used to be a Swan.

Carmina Burana is a classical music work, composed by Carl Orff, and means “Songs from Beuren”. Composed in 1936, and premiering at a time where Germany’s Nazi regime fearfully awaited the public’s reaction to the semi-erotic nature of the work, Carl Orff’s position towards the State was immediately aligned. Lending his artistic genius to –partially- serve some of the regime’s performances of power, Carl Orff was not one of the artists attacked by the Nazi regime in its years of ascension. Alex Ross, the music critic at the New Yorker magazine since 1996 argues in his essay on WWII music that ethics and aesthetics are not always tied together perhaps.

“But it is unwise to look for too much sinister meaning here. Strauss and Orff were assiduously cultivated by the Nazi regime not because they had exceptional sympathies with the Nazi movement, but because they had a self-evident power to affect broad audiences. Their surrender to Nazi overtures is an ineradicable stain on the biography of each; but the music itself commits no sins simply by being and remaining popular. That “Carmina Burana” has appeared in hundreds of films and television commercials is proof that it contains no diabolical message, indeed that it contains no message whatsoever.”[7]

For Alex Ross, having no message whatsoever is a good sign, even if one did not resist a regime as diabolical as the Nazi regime in Germany. He continued in the same article to wonder about righteousness: “What is the measuring-stick for righteousness in this time? Who acted justly?” The ones who did not offer anything for the lusty imagination to gnaw on.

In Venus in Furs, Leopold Von Sacher-Masoch brings us to a line that could answer to Alex Ross’s questions. “You have corrupted my imagination and inflamed my blood...”. Written by an expert in law, Masoch brings us to think of the moments a body confronts law, and hence of choreography as a set of laws, both in the sense of laws of physics, and both in the sense of a mesh of legally binding articles. It is through the practice of Egyptian choreographer/dancer Amie Sultan that we could further elaborate on law and dancing bodies, in relation to Statehood performance of power masquerading under the notion of public decency.

Von Sacher-Masoch invites us through his iconic novella to nuance the relation of modernity to indecency, and the role that middle class has to play in such operations of production of value and of policing bodies. Policing in the Rancierian sense, as well as policing as acts practiced by the State in order to protect its tightly knit web of lies. In 2011, right after the beginning of the Egyptian revolution, a young star of the Cairo Ballet Company abruptly quit the Opera House, at the peak of her career. The young star that was touring internationally both with the Ballet Company of the Cairo Opera House, and with visiting international choreographers decided to abandon the ‘house’. In opposition to the politics of the house in relation to the State

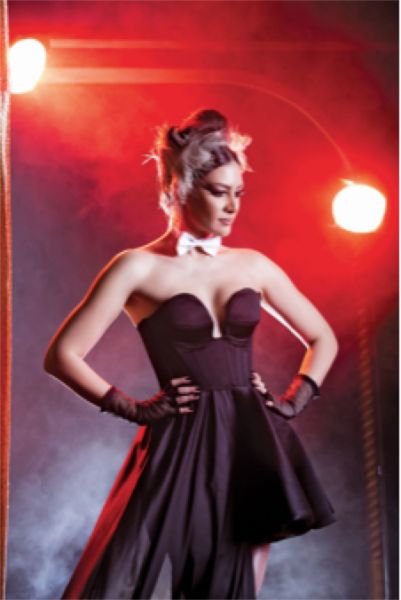

Amie Sultan as the Belly-dancing Black Swan

politics, and in opposition to the roles that will be imposed on her now that the State needs to perform something even more ‘perfect’ than Classical Ballet, Amie Sultan decided that the only dance she wishes to continue performing after the fall of Mubarak –and within a turbulent propagandist cold war. A cold war between the 60 year old post-Nasserist military regime and the post-Sadat’s Wahabist Islamists; both invested in nothing but performing social propriety and appease the middle class ethics that in the light of the shocking majority of the ‘actual’ inhabitants of the capital, may be the last resort to support the crumbling senile state. Sadat’s/ Mubarak’s middle class my keep the regime erect beyond its ‘Naksa’.

In her grand exit of the Opera House, Amie Sultan announced she will dance in cabarets and nightclubs. While Cabarets are legal in Egypt, they are also sites of power controlled by the police, and by the State, to produce certain narratives at certain points in time since the onset of the so-called Police State with the regime of Sadat. A narrative that the body and the subject that is Amie Sultan challenges. She is not a poor, under-educated, clandestine life from outside of the capital, who ‘had to do it’, and had to join the dark world of cabarets. She gracefully walked there willingly, from her very rich family background, high education, stardom position at the Opera House. For Amie, that move was freedom of choice. For the authorities, that was public shaming to Egyptian cultural institutions, to the high dance education that she had received, and to the choreographies the regime wished to use her body to perform. The choreographic insight here is perhaps somewhere within the shades of being fallen and that of willing a fall and commanding it.

With the State producing narratives on public decency that culminate into imprisonment of Egyptian artists and intellectuals in a neo-witch-hunt context, it is vital to ask who the public is and what decency is. The question of contemporary dance education in Egypt would also need us to problematize; whose contemporaneity are we referencing, and whose dances are we propagating? But with at least 65% of the citizens of Cairo living in another unofficial Cairo that gives birth to baladi-dance performances, local economic circuits, and experimental music genre such as ‘Mahraganat’, the question on the public seems less important. What is urgent to address is how this Foucauldian systematic stigmatization and othering of one massive part of the social fabric, and the demonization of the clandestine dance scene, is itself the pornographic. That the pornographic is not the Contemporary Dance Centre in Cairo that the Muslim Brotherhood sought to shut down repeatedly, eventually with success. But the pornographic is produced when the state others a massive part of its fabric, and stigmatizes their dances. It is there in the selective light shedding and light dimming that the pornographic is produced. The pornographic is not merely full display of acts deemed indecent, but rather than careful light design between showing and concealing, and between what’s deemed private or public. For it is not produced through full clarity and full nudity; for the pornographic to exist such extremely careful manipulation of light and dark, of clad and undressed must be performed by panicking regimes. The question then re-articulates itself through this mesh of actors: The Good State, The Dancing Whores, and The Ignorant Thieves. The notion of public decency is hence an operation of the State not to protect the ‘ideal citizen’ and their feelings and ethics, on the contrary. The notion of public decency is an operation of the State to generate the pornographic as a propagandist tool of deflection and decoy, at times where humane interventions are needed to make life possible again, within a necropolitical reality, where a country has been transformed through decades of military autocracy, wars and economic crises into a wasteland.

imageID: 6570}

Dancing young men in one of the vilified informal settlements during ‘Mahraganat’ concerts

Yet, could the practice of Amie Sultan offer us a choreographic insight into the pornographic that is invoked and performed by panicking States? In one of her many self-choreographed and self-performed solos, true to the nature both of Baladi-dance historically but also to an understanding of the term choreography set within a genealogy of archaic performance practices; Amie Sultan went down to the floor into a split, and started doing floor work. Her classical dance education and Baladi (Belly) dance one, were re-inscribed through her body into a third dance material. The incident was reported to the authorities, and the next day her show was stopped as she was just going into a split again. The officer produced a document that he carried that stated that belly dance was an erect dance form that has no floor work in it, and hence she has no right to go down to the floor at this cabaret.

The costumes worn by Amie Sultan that are tasteful and very revealing were never the object of legal attacks against her, nor her extremely playful looks and performance tricks and erotic presence. Her display of herself as an ultimate erotic fantasy was never a crime. What in this mere movement of going down to the floor terrified the State that they decided to come after this dancer? Is it that it could possibly be ridiculing the Cairo higher institute of Ballet? Is it demeaning the virginal de-eroticized nature of what the Egyptian authorities decided classical ballet is, in relation to other forbidden carnal dances such as contemporary dance?

A very similar question is the case of Syrian poet (who was also a diplomat) Nizar Qabbani who was renowned for his erotic poetry in the late 20th century. The attacks that were raged against him were when he wrote about lesbian sex, in one of his radical poems describing the encounter between two pairs of female breasts where he used the word “ebaha” which means to reveal a secret, but also denotes the pornographic as it invokes the semantic field of the word root. In his poems, the four breasts in proximity ‘revealed’ secrets to one another about desire, mutual lesbian desire in this case, that was held secret. In the attacks against him, the word was used for its semantic field, the way the words of Ahmed Naji were held against him earlier in 2015, bringing the State to sentence him two years in prison.

What is it then that makes it ok to describe the sexual act of a man and a woman in Qabbani’s poems, but not the poetically abstracted lesbian act? What is it in Naji’s choice of words that was more offensive than the poverty line in Egypt, or child labor? Or organized rape? What is more disturbing to public morality: intercourse described in lavish details, lesbian nipples whispering like doves, beer and oral sex, revealing costumes and splits? Again, I argue that such question may not be politically pertinent to pose, as such attacks do not stem from the public nor involve the public as an active actor. Such attacks are staged State performances that aim at producing the pornographic.

To rethink the argument from a dance perspective: What is it that makes it ok to display oneself as a sexual object in the cabaret but not to go down in splits in the case of Amie? Why are we taught that it is ok for an Egyptian woman to show her legs in Ballet and not in Belly Dance? Why do Egyptian dance institutions have no problem with men in extremely tight pants parading their crouch on a Ballet stage, but not let them explore their physicality in contemporary dance classes? Could it be that what the military now defines as pornographic is female sexuality itself? The power a woman gives herself to be sexual as in opposition to making oneself available sexually as an object to look at? Could it be the different relations to gravity, from being fallen, to having the agency to fall when one desires and be erect when one desires, in the face of a State-of-Naksa?

I believe that both the military regime and the police forces here give us a choreographic insight into what the pornographic is seen through dance: It is the going down to the floor when you are expected to be erect. It is the breaking free from aesthetic regimes, it is the displacement of bodies within other spaces of alterity, it is the performance of what is seen as a ‘representative body of the state’ within sites that are not part of the official discourse, but are used by the official apparatus to regulate power, bodies, desires and policy. It is the refusal of the erotic and the engagement in the technical physical virtuosity of dance, in a space deemed sexual by the State. A state that legalizes opening cabarets that cater for prostitution, but would shut down contemporary dance schools.

If words have semantic fields, movements have corporeal fields. And, the splits practiced by Amie Sultan is the rejection of the pretense that modernity is erect, quiet and graceful, while using the lexicon of a practice like Classical Ballet that came to Egypt as an act of ‘modernisation’ from the West, and also is one of the few ‘official dances’ allowed to be performed in State institutions, where splits are possible on national theatre stages. The pornographic choreography that upsets the middle class ethic is that of becoming embodied, fully desirous and in negotiation with gravities as a woman in Egypt now, or as a queer man.

Is it the same political logic that Josephine Baker had when she decided it is ok to dance naked but not ok to demand sexual Liberty, and hence she could march against the May 1968 uprising? Is it why it is ok for the Egyptian government to legalize cabarets but shut down dance festivals?

Amie Sultan's choreography, and her political position were in the exact opposite nature and direction in relation to Josephine's. Amie walked out on the official narrative of what good and bad was and decided to go dance beyond good and evil, meditating on Nietzsche. While Amie’s dance education and ideological position complicated that of the state, Josephine made it simple for us. To be good is to be modern, and to be modern is to be De Gaulleian and to be white and to be sexually repressed yet penetrable. Her position performed everything the opposition of De Gaulle meant on the uprising.

The regime as a choreographer of propriety said to Amie: show me your thighs, lift those legs high, tip toe and don't you make any sounds or voices. Do it all while moving sideways and looking away from my eyes. Do it at the National Theatre to a bourgeois public. Amie preferred another choreography, where she shimmies and never shivers, and when she shivers she looks straight into our eyes, she preferred to bend her spine in any direction she may please, undulating, and when need be, remind us of gravity, and joyfully sink into it with a very open pelvis, all while making sounds and voices. All while raising hell and projecting her voice through Zaghareet, all while always being able to make the choices herself; the choice to stay or to leave a political establishment, the choice to corrupt the imagination and flame the blood of the viewer or to tiptoe, the choice to stand and to fall and to repeat this dance as many times as necessary.

Wanda said to the ‘author’ in Venus in Furs: “Once I no longer exist as I am, out of what consideration then should I forgo anything? Should I belong to a man I don't love simply because I used to love him? No, I forgo nothing, I love any man who appeals to me and I make any man who loves me happy. Is that ugly? No, it is at least far more beautiful than my cruelly delighting in the tortures incited by my charms and my virtuously turning my back on the poor man who pines away for me. I am young, rich, and beautiful, and just as I am, I live cheerfully for pleasure and enjoyment.”

Just like Cairo, Amie once upon a time lived by the lake, once upon a time was seen as beautiful, only when she was a swan. Before she even gets to dance her new dance, in cabarets, or like Maharaganat female and male performers with knives and scissors on the streets of the ‘paratopia’, a military choir with a deep voice answered; “Miser, Modo Niger, Et ustus Fortiter”

Choir…

Between 1971 and 2016, L’Institut D’Egypte, The National Theatre of Egypt, The Theatre of Beni Suif, The Cairo Opera House, the Abdeen Archives on Cairo were all set on fire, mysteriously.

[1] Translation: Once I lived by a lake, Once I was seen as beautiful, When I was a Swan.

[2] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

[3] From Latin; Lupus, referring to its previous site as wolf-hunting den- Grand Larousse Encyclopedique

[4] Naksa: loss at war (Arabic). A term that opens a semantic field on loss, erectile dysfunctions, depression, going low, being low

[5] Marion Sejourne’, The History of Informal Settlements: About Cairo and its informal Areas.

[6] Sawsan Gad, The Future of Egyptians, Cairography Publication, January 2014 http://sarma.be/docs/2951

[7] Alex Ross, “In Music, Though, There Were No Victories”- The New York Times, Aug. 20, 1995